What makes a country rise to the top of the ‘Good Country Index’, is how much it contributes to the welfare of the entire planet. Conversely a ‘bad’ country does the opposite. The Index measures how much each of the 163 countries on the list contributes to the planet, and to the human race, through their policies and behaviors.

Most governments feel that their responsibility is to their own citizens, not the planet. ‘Make my country great again!’ is what many leaders hear from the people who voted for them. But often, this means that other countries, including the planet itself, are getting worse in the process. Anholt advocates for a new ‘culture of governance’, which he calls ‘the Dual Mandate’.

“One day soon, the casual nationalism that characterizes almost all political and economic discussions will seem as outdated and offensive as sexism and racism do today. Leaders must realize that they're responsible not only for their own people, but for every man, woman, child and animal on the planet; not just responsible for their own slice of territory, but for every square inch of the earth's surface and the atmosphere above it.” (From the Good Country website).

This, in fact, makes Anholt’s Index the first global ‘watchdog’ of its kind.

It really makes a lot of sense, since the most important challenges facing humanity right now are global in nature: Problems like global warming, migration, human rights and poverty, do not recognize borders; they cannot be solved on a national level, no matter how well-off a country is. The Good Country Index is interested in how MUCH countries are doing, not how WELL countries are doing.

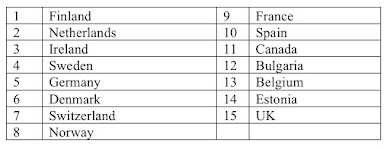

Still, there is a correlation between what a country does for its own citizens and what it contributes to the planet. The 15 ‘goodest’ countries, as Anholt calls them, all have a strong welfare system (and high taxes to pay for it). They are good internally and externally. Here is the list:

The Index is based on a vast amount of data and is not to be confused with other indexes which measure a country’s quality of life or its level of inequality (the Gini Index). The Good Country Index, which is grouped in 7 sections, rates countries relative to its GDP. A small country like Holland, which was ranked as ‘the Goodest Country’ in 1918, contributed .99% of its GDP to foreign aid far more to Global welfare than many other much larger economies.

Much of what Anholt includes in his index overlaps with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), set by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, intended to be achieved by the year 2030. This includes the usual suspects: no poverty, zero hunger, good health, good education, clean water, decent work, climate action and peace and justice.

What is depressing, is that of the 20 largest economies in the world, only half are among the top 20 Good Countries. The 4 largest economies, (the US, China, Japan and India) have a combined GDP that far surpasses that of the 20 Goodest Countries. (See: List of development aid country donors.)

On the other hand, it is not all about the size of a country’s economy. Anholt talks about a country’s ‘branding’. America after two World Wars, was the goodest country by far. It pulled Europe out of a sink hole, rewarded its enemies by giving them aid and had it not been for this country’s sacrifice, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing about it. America was the best thing that the world needed at the time. What happened? Can the US repair its tarnished image? It has the resources to do what Anholt calls ‘the Dual Mandate’, but it hesitates. *

The Good Generation Project>But people (and their governments) behave the way they have been told. We still think nationally, we still behave as if countries were closed societies. It is very hard to change the behavior of an adult, but children are different. In this context, Anholt quotes the Jesuits as saying: ‘Give me the boy and I will give you the man’. That is why he has created the Good Generation Project, suggesting that 200 or so international Ministers of Education meet and create a blueprint that could be streamed all over the world.

Anholt has a problem with NGOs and charities that all use the same phrase ‘we must leave the world in a better state for our children’. As if our generation can fix something that has taken hundreds of years to take shape. It will take at least a generation to replace our psychological and social DNA. He suggests that Universities are the ideal partner to create a bridge between governments and our children.

The Goodest LeadersOn his website, Anholt also has a list of ‘Good Leaders’. When I saw Jeff Bezos listed as a ‘goodest leader’, I was surprised. Anholt explained that Bezos’ recent $10 billion pledge towards Climate Change. Although he is far from good at paying his fair share of taxes, this gesture will hopefully encourage him to be an even ‘gooder leader’. However, Bezos was already the richest man in the world last year, with about 60 Billion. This year, he has doubled his wealth to 120 billion. To select him as a “goodest leader” is absurd.

There is some criticism of the Good Country Project, mostly on how it measures a country’s ‘goodness’. In the Science and Technology section, for instance, a country is rewarded for how many patents it has applied for. But owning a patent can sometimes harm the common good. When Jonas Salk, the inventor of the polio vaccine, was asked who owned the patent on the vaccine, he replied: ‘Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?’

The GCI Index also penalizes countries for generating refugees. But what if it is through no fault of their own, like famine or drought? Bad luck shouldn’t be confused with bad behavior. It also penalizes countries with high rates of population growth. Even though the population explosion in Africa and India does not help improve either the world or those countries themselves, there are some countries that would benefit from a higher birthrate, especially the ‘good countries’.

All in all, I have great admiration for Simon Anholt. He is a David trying to take on Goliath. But of course, he is right. The problems the world faces are too big and too complex for any individual country to solve. If nations don’t start collaborating instead of competing against each other, we are in big trouble. This is why the Good Country Index exists. leave comment here

* In light of the most recent Climate Change Summit, hosted by President Biden, in which the US pledges to cut its global warming emissions in half by the end of the decade, America’s ranking on the Good Countries List should move up the list drastically. The US’ international reputation is still so high that this very significant step will hopefully have enormous consequences.